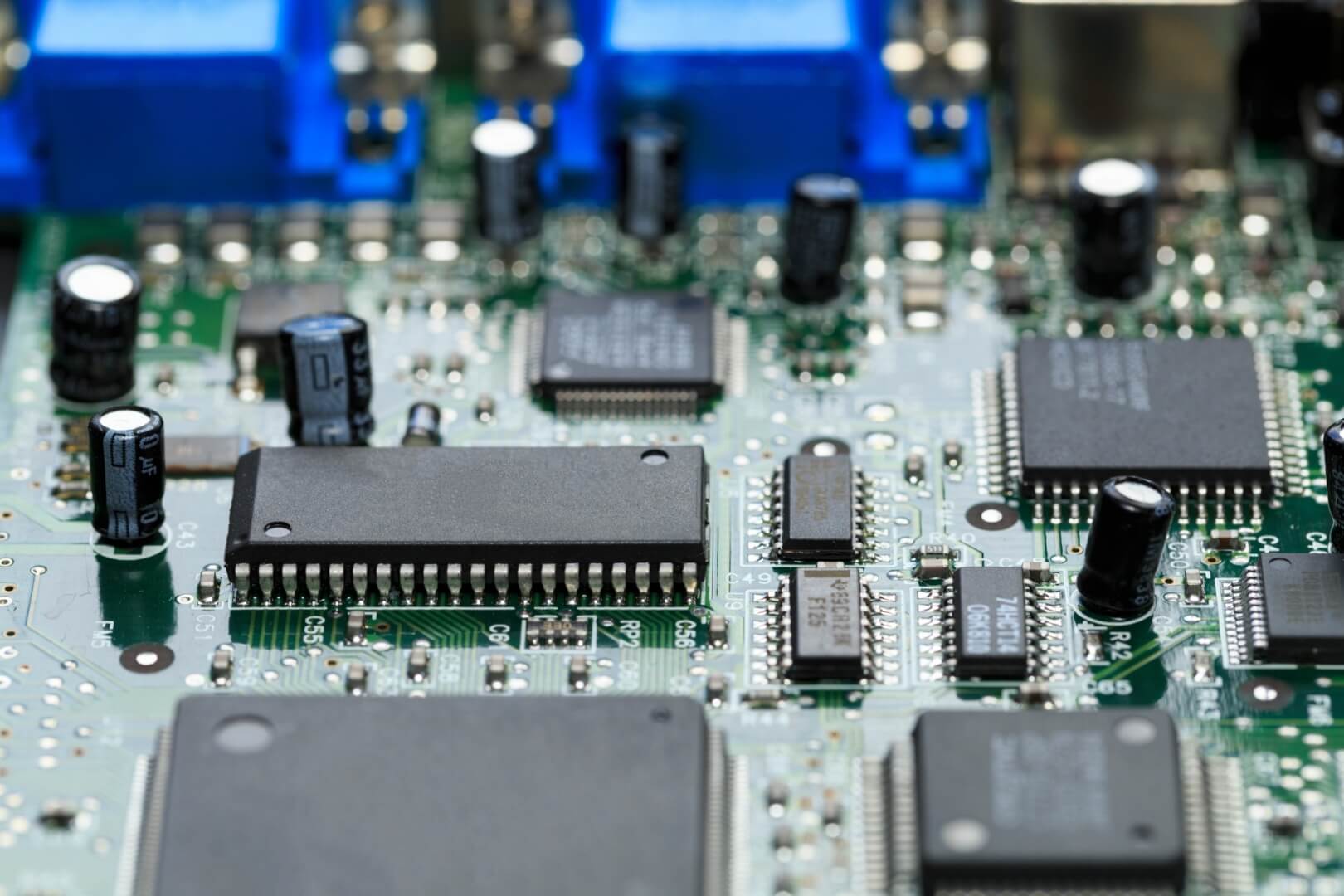

The United States is looking at various strategies to address the semiconductor workforce gap. According to a report recently released by the Semiconductor Industry Association and Oxford Economics, the United States is projected to face a shortage of 67,100 technicians, computer scientists and engineers throughout the semiconductor industry, and 1.4 million across the nation’s economy by 2030. Semiconductors enable critical technologies that help encourage economic growth and improve national defense. The report predicts the semiconductor industry will require a total of 238,000 technicians, computer scientists and engineers by 2030. They warn that without acting to address the semiconductor workforce gap, the United States will fail to achieve its full potential of capacity growth, supply chain resiliency. and technology innovation leadership.

The report recommends semiconductor companies look toward regional partnerships and programs that can help to grow the talent pipeline for skilled technical roles in semiconductor manufacturing and other advanced manufacturing sectors. In order for 80% of technicians to obtain credentials, it can take six to 24 months to acquire. Due to this, semiconductor companies are looking to develop and expand programs in order to recruit and teach skills to new workers. In addition, the report recommends a comprehensive STEM strategy that begins with encouraging students to work in a STEM profession and making them aware of job opportunities in the semiconductor industry. They also suggest the need to retain and attract more international advanced degree students within the U.S. economy, since the workforce gap cannot be realistically addressed solely with citizen graduates by 2030. Here is an opinion piece we found of interest relating to how to address the semiconductor workforce gap.

Worries over skills gap overshadow US jobs boom

In an opinion piece “Worries over skills gap overshadow US jobs boom” for Financial Times, Taylor Nicole Rogers, correspondent, discusses the Biden administration’s investment in new industrial projects, such as building electric vehicles and assembling semiconductors, through the Inflation Reduction and Chips and Science acts. Intel, Micron, Analog Devices, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company are among the companies that have pledged to spend over $200 billion on more than 100 projects and thereby create tens of thousands of jobs, taking advantage of billions of dollars in federal subsidies.

Rogers reports that semiconductor companies are hiring as fast as they can, but the semiconductor specialized jobs require investment in workforce training. They claim as many as 58 per cent of the 115,000 positions the semiconductor industry is predicted to add by 2030 may not be filled. According to the Semiconductor Industry Association, this is due to the relatively small number of students who complete degrees in engineering and other science and technology subjects. Jin Yan, an economist at workforce intelligent group Revelio, claims these roles require very different skills to those in traditional manufacturing. According to Yan, the specialized work can also make it difficult for staff to transition to new jobs in a semiconductor fabrication plant.

Many semiconductor companies are looking at developing their own workforce training for these semiconductor specialized jobs. For example, Massachusetts-based Analog Devices, which is building a $1 billion semiconductor wafer fabrication plant in Beaverton, Oregon, has developed an eight-week semiconductor manufacturing class designed to transition military veterans, and people re-entering the workforce into careers at the plant, as well as upskill existing employees. Meanwhile, Intel has partnered with community colleges near its Ohio fabrication plant to create a one-year semiconductor technician certificate program. The majority of Intel’s semiconductor specialized jobs will require a two-year associate degree with the pay of $50,000 and $60,000 on average, and include full medical benefits, as well as paid parental leave and sabbaticals. Read more on Financial Times.

Disclosure: Fatty Fish is a research and advisory firm that engages or has engaged in research, analysis, and advisory services with many technology companies, including those mentioned in this article. The author does not hold any equity positions with any company mentioned in this article.

The Fatty Fish Editorial Team includes a diverse group of industry analysts, researchers, and advisors who spend most of their days diving into the most important topics impacting the future of the technology sector. Our team focuses on the potential impact of tech-related IP policy, legislation, regulation, and litigation, along with critical global and geostrategic trends — and delivers content that makes it easier for journalists, lobbyists, and policy makers to understand these issues.

- The Fatty Fish Editorial Teamhttps://fattyfish.org/author/fattyfish_editorial/January 19, 2024

- The Fatty Fish Editorial Teamhttps://fattyfish.org/author/fattyfish_editorial/January 3, 2024

- The Fatty Fish Editorial Teamhttps://fattyfish.org/author/fattyfish_editorial/January 3, 2024

- The Fatty Fish Editorial Teamhttps://fattyfish.org/author/fattyfish_editorial/December 31, 2023